“We may be hitting on one of those ‘lost secrets’,” says Linda Eneix, President of The OTS Foundation, dedicated to archaeology research and education related to the ancient temples of Mediterranean Malta.

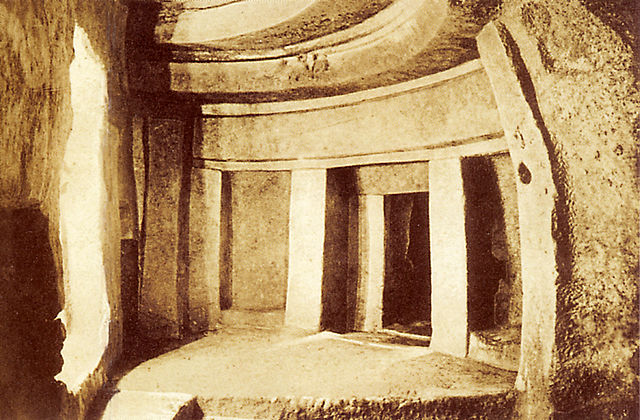

Located south of Sicily, the islands of Malta and Gozo are home to megalithic structures that were created by a highly developed people more than a thousand years ahead of Stonehenge and the pyramids. The monuments, including ancient temples, represent free-standing architecture in its purest and most original form. Design features including corbelled ceilings, are mirrored in subterranean mortuary shrines that have been carved out of solid limestone. (In architecture, corbelling is a system of a row of stones oversailing the one below it, reducing the area of the ceiling with each row upward and distributing its weight.) Malta’s Hal Saflieni Hypogeum provides the most extraordinary example. A multi-leveled complex of caves and ritual chambers, it is a gem of archaeology that lay undisturbed until workers broke into it accidentally in 1902.

Science Officer at the Hypogeum, Joseph Farrugia describes unusual sound effects in the UNESCO World Heritage Site: “There is a small niche in what we call ‘The Oracle Chamber’, and if someone with a deep voice speaks inside, the voice echoes all over the hypogeum. The resonance in the ancient temple is something exceptional. You can hear the voice rumbling all over.”

As anyone who sings in the shower knows, sound echoing back and amplifying itself from hard walls can do unusual things. That effect is magnified several times over in the stone chambers. “Standing in the Hypogeum is like being inside a giant bell,” says Eneix. “You feel the sound in your bones as much as you hear it with your ears. It’s really thrilling!”

After catching a film about the “Sounds of the Stone Age” on a flight from London, Eneix jumped on the chance to explore further and sought out the principals.

A consortium called The PEAR Proposition: Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research are pioneers in the field of archaeo-acoustics, merging archaeology and sound science. Directed by Physicist Dr. Robert Jahn, the PEAR group set out in 1994 to test acoustic behavior in megalithic sites such as Newgrange and Wayland‘s Smithy in the UK. They found that the ancient chambers all sustained a strong resonance at a sound frequency between 95 and 120 hertz: well within the range of a low male voice.

In subsequent OTSF testing, stone rooms in ancient temples in Malta were found to match the same pattern of resonance, registering at the frequency of 110 or 111 hz. This turns out to be a significant level for the human brain. Whether it was deliberate or not, the people who spent time in such an environment were exposing themselves to vibrations that impacted their minds.

Sound scientist, Prof. Daniel Talma of the University of Malta explains: “At certain frequencies you have standing waves that emphasize each and other waves that de-emphasize each other. The idea that it was used thousands of years ago to create a certain trance — that’s what fascinates me.”

Dr. Ian A. Cook of UCLA and colleagues published findings in 2008 of an experiment in which regional brain activity in a number of healthy volunteers was monitored by EEG through different resonance frequencies. Findings indicated that at 110 hz the patterns of activity over the prefrontal cortex abruptly shifted, resulting in a relative deactivation of the language center and a temporary switching from left to right-sided dominance related to emotional processing. People regularly exposed to resonant sound in the frequency of 110 or 111 hz would have been “turning on” an area of the brain that bio-behavioral scientists believe relates to mood, empathy and social behavior.

Although archaeologists had not found an explanation for such sophisticated engineering suddenly blossoming nearly six thousand years ago, Prof. Richard England, a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, sees an evolution: “. . . a gradual growth, from the cave to the tomb. The idea of continuity comes from an underground architecture. Gradually from these ovular rock-hewn spaces, man moved above ground, and above ground he fashioned an architecture of the living which followed the form of an architecture for the dead.”

“Once you know what you are looking for, you can see these same ceiling curves in natural caves in Malta.” Eneix observes. “It’s logical that the ancient temple builders observed the echoes and sound characteristics in the caves and came up with the idea of recreating the same environment in a more controlled way. Were they doing it intentionally to facilitate an altered state of consciousness? There is a lot that we are never going to know.”

Acoustics may well have been part of a widespread religious tradition. Old photos in an early edition of National Geographic Magazine show the discovery in securely dated levels of the Malta temples, of conical shaped stones bearing a distinct resemblance to the Omphalos or “belly-button” oracle stone at Delphi, used much later in time by ancient Greek priestesses who listened to the voice of the earth for guidance. The Omphalos became an Umbilicus when the Romans took over the concept and spread it over their empire. The timeline places the ancient Temple Builders at the head of a long chain of “coincidence.”

Research about Malta’s Temple Culture has been documented on a DVD available from the foundation at http://www.otsf.org/Legacy.htm. This captivating documentary details how inquiry into ancient temples in Malta mirrors the evolution of a discovery, branching beyond archaeology to become a multi-disciplinary fascination.