Carvings disovered near Avebury linked to spring fertility celebrations

by Terence Meaden

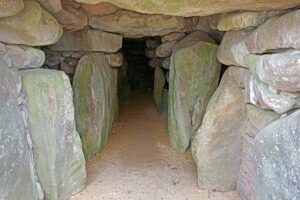

West Kennet Long Barrow – near Avebury and Swallowhead Spring and in sight of Silbury Hill – is one of Britain’s best-known chambered monuments. It was built on a hill by the Ancient Britons over a mile south of Avebury around 3600 BCE (plus or minus a hundred years) and was closed down about 2400 or 2300 BCE.

West Kennet Long Barrow – near Avebury and Swallowhead Spring and in sight of Silbury Hill – is one of Britain’s best-known chambered monuments. It was built on a hill by the Ancient Britons over a mile south of Avebury around 3600 BCE (plus or minus a hundred years) and was closed down about 2400 or 2300 BCE.

The barrow consists of a central gallery open to the east, with a cell at the western end and two cells off each side of the gallery. Over 40 standing stones were used in its construction – sarsen stones like the ones used at Stonehenge and Avebury – together with numerous capping and corbel stones in the roof. Excavations revealed large numbers of human bones and simple ritual objects and positioned skulls, because of which most archaeologists refer to it as a tomb of the dead and declare it to be a monument where bone portage and morbid funeral practices were carried out. When it was taken out of use, the barrow was filled in and huge blocking stones set in place.

However, it is much more than a tomb. It is a death-and-rebirth tomb-temple involving the proven presence and influence of the Earth Mother which makes it a far more significant monument than hitherto suspected. For inside the main chamber and gallery are carved human heads of such subtlety that they have gone unnoticed during the 43 years that the barrow has been open to the public. Two years ago I brought world attention to the huge yoni or vulva symbol carved on the outside of the central blocking stone at the eastern end of the monument. This feature is a long vertical hollow 5 feet 3 inches (160 cm) long and 20 inches (50 cm) wide at its maximum, and it is the sixth prominent Neolithic yoni that I have found on megaliths in the Avebury region. Today I announce the discovery of a sequence of carved human heads and one sheep’s head for the interior of the monument.

However, it is much more than a tomb. It is a death-and-rebirth tomb-temple involving the proven presence and influence of the Earth Mother which makes it a far more significant monument than hitherto suspected. For inside the main chamber and gallery are carved human heads of such subtlety that they have gone unnoticed during the 43 years that the barrow has been open to the public. Two years ago I brought world attention to the huge yoni or vulva symbol carved on the outside of the central blocking stone at the eastern end of the monument. This feature is a long vertical hollow 5 feet 3 inches (160 cm) long and 20 inches (50 cm) wide at its maximum, and it is the sixth prominent Neolithic yoni that I have found on megaliths in the Avebury region. Today I announce the discovery of a sequence of carved human heads and one sheep’s head for the interior of the monument.

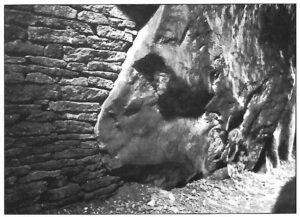

The latter is located at the base of a gallery stone to catch the light of the pre-equinoctial rising sun. It is a skillfully-crafted head of a ewe, carved in relief in left-facing profile. Much of the stone is a reddish colour and fairly smooth but with a lightly-pitted surface, while the section which has been sculptured, close to the ground, has a whiter hue. About an inch depth of stone was removed to create this sculpture in bas-relief.

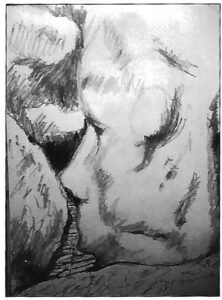

The best head is on an east-facing stone in the western chamber. This is a left-facing human head in relief and profile, with perfect physical proportions. As I explained in The Goddess of the Stones left-facing features, indeed anything left-handed in the beliefs of traditional societies, imply femininity. As a consequence, I suggest that it is an icon of the female divinity of the tomb-temple, namely, the Temple Goddess carved with such care and finesse that no-one but the initiated – those who understood and adored the Neolithic Earth Goddess – would know it was there. And being on the western wall the rising sun illuminated it at the March equinox for a thousand years or more before the barrow was sealed. At this auspicious time of the year she was the Spring Fertility Goddess.

In her book The Earth Goddess Cheryl Straffon describes how the Goddess of Winter, in the eternal round of the seasons, becomes the Goddess of Spring. This leads us to ask whether the next megalith taken clockwise round the end-cell of the tomb-temple might represent the Winter Goddess; and indeed inspection suggests that the stone has the shape of a left-facing skull with a dome-topped cranium and left-side cavity typical of a skull’s noseless hollow. This stone (like the ewe’s head) would receive the pre-equinoctial mid-March sun before the female Human Head Stone gets the late-March sun. Moreover, and surely meaningful in terms of intentional young-life symbolism, was the discovery by Dr John Thurnam in 1859 of “the chief part of the skull of an infant about a year old” which had been placed between the upright edges of these same two megaliths precisely in line with the gallery.

The three stones together tell a story.

The ewe’s head faces the other two heads. It recalls the Imbolc lambing-festival which falls in early February (Imbolc) the time when oi-melg, or ewe’s milk, begins to flow, and is the Herald of Spring. Because the barrow faces east, the order in which the sunlight falls first on the Skull Stone before reaching the Spring Goddess Head shows that the transition from Winter Goddess to Spring Goddess was planned into the mural sequence, proof that the ancient Britons were celebrating the Rites of Spring as early as 3600 BCE.

In the south-west chamber is a megalith with three cup-depressions near the top. Three cups hint at the presence of the triple goddess because it was in this chamber in 1955-56 that Stuart Piggott found that “three skulls had been arranged against the south wall” in a row: the skulls of a child, a young woman, and an elderly woman, alluding to the three ages of woman.

Along the northern interior of the barrow, inside the forecourt and gallery, there is a sequence of at least five additional sarsen stones, all with human heads in left profile. Some are easy to see, but others require the illumination to be just right, their detection needing oblique lighting as if from the rising sun. Nine heads have been detected so far, and more may yet be found.

The rediscovery of these lost images has considerable consequences for rebirth theories and the understanding of the spiritual motivation behind the construction of megalithic long barrows.

About the author:

Dr. Terence Meaden is an archaeologist from Oxford University. He has studied the megalithic period of British prehistory in depth, and has deduced much about the Earth Mother fertility religion of the epoch. His books, published by Souvenir Press, London, include: Secret of the Avebury Stones and Stonehenge: The Secret of the Solstice

. His website is www.stonehenge-avebury.net/megaframes.html

This article was originally published in the April/May 1999 issue of Power Trips magazine.

Photo credits:

West Kennet Long Barrow entry: Troxx, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

West Kennet Long Barrow interior: Tomw37, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons