by Glenn H. Mullin

Lhasa, Tibet! When as a young man I first saw this name on a map, a warm current of electricity rose up my spine. Images of levitating lamas, yogis in caves, the high Himalayas and abominable snowmen drifted through my mind like holographic clouds on a summer day. I started reading whatever I could find that had anything to do with the place.

Lhasa, Tibet! When as a young man I first saw this name on a map, a warm current of electricity rose up my spine. Images of levitating lamas, yogis in caves, the high Himalayas and abominable snowmen drifted through my mind like holographic clouds on a summer day. I started reading whatever I could find that had anything to do with the place.

I learned that Tibet had been taken over by Communist China in the 1950s, that the Dalai Lama and many of his people had fled over the mountains to the south and now lived in India as refugees, and that all but a dozen of Tibet’s 6,500 monasteries and temples had been destroyed during China’s cultural revolution. Communist China had closed Tibet to outsiders, but one could meet the Dalai lama in India. My wife and I packed our bags and made the journey from Amsterdam to Dharamsala, India, and into the Dalai Lama’s presence. We remained in Dharamsala training in Buddhist knowledge for the twelve years to follow.

In the early 1980s a policy of liberalization swept across China. The roads to Tibet were once more opened up to foreigners, and Lhasa again became accessible to pilgrims. The few remaining temples and monasteries were allowed to re-open, and hundreds of those that had been destroyed were quickly re-built. The Tibetans are enthusiastic builders (or, in this case, re-builders), and Tibet today has almost a thousand active spiritual institutions.

The Tibetan name “Lhasa” has two components: Lha, which means “the gods,” and sa, which means “earth” or “place.” The Tibetans are a shamanic people, and hold geomancy as one of the high sciences. In one sense all places in the world are equally sacred: but from another perspective there are certain sites where heaven and earth come into a special harmony. These are meeting place of humans and the gods. The Tibetans call such a place a Chinlab gyi Ney, or “Site with Waves of Power.” The earth is the great and wonderful body of the Earth Spirit; power sites are like acupuncture points on that body. When humans visit a power site, the primordial seeds of esoteric knowledge that lie quietly on the deeper levels of the mind are mysteriously aroused and awakened. Lhasa is one of the five most important such places in Asia.

There are many ways to get into Lhasa these days, although political conditions change constantly in accordance with the whims emanating from Beijing. The cheapest is probably via Hong Kong, and then overland to Chengdu, China’s military headquarters for the administration of Tibet. Chengdu has many travel agencies that put together instant groups travelling to Tibet. Officially one has to be part of a group of at least five people, but many travelers make it in as “a group of one.” Entrepreneurship has come to Communist China with a vengeance.

Another popular route, albeit slightly more expensive, is via Katmandu, Nepal, from where one can fly to Lhasa or go in overland. This route has several advantages, not the least being the beauty of Nepal as compared to the ugliness of utilitarian Communist China. Nepal and Tibet share many spiritual roots, so Katmandu also provides a good introduction to the Tibetans.

My own preferred way of making pilgrimage to Lhasa is to fly in from Katmandu and then bus out overland. The flight takes one over the southern Himalayas, with the plane passing within sighting distance of Mt. Everest. The drive out takes one by the sacred Turquoise Lake, on to Shigatse, and then directly through the Everest region, where the eleventh century Tibetan yogi Milarepa composed so many of his mystical songs and poems.

The Lhasa Valley is located at an altitude of approximately 12,000 feet. The air is thin at this height, and as a result colors take on a whole new vibrancy. The world comes through like a scene from a Bertoluchi film. Lama Govinda, whose Way of the White Clouds provides a wonderful introduction to this magical land, wrote that perhaps it was this closeness to the heavens and the resultant effect on the senses that had made the Tibetans so profoundly mystical a people for so many centuries.

The road into Lhasa runs by the Kyichu River. This amazing body of water begins its journey far to the West on the legendary Mt. Kailash, power site of the Hindu god Shiva, and also the source of both the Indus and Ganges rivers. The Kyichu is given different names in different sections of its journey, but eventually it flows east from Lhasa and then cuts a path south through the Himalayas, to emerge in India as the Brahamaputra, or “Son of Brahma.” Brahma, of course, is the Indian name for God the Creator; Shiva is the name of God the Destroyer. This river, then, is the rebirth that comes from death, an embodiment of the process by which death constantly re-emerges as life. It is the source of life in the Lhasa Valley, and an important element in the valley’s sacred geomancy.

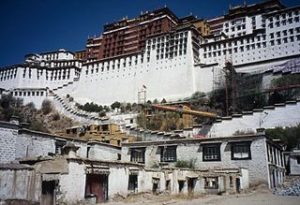

All approaches into Lhasa provide a stunning view of the Potala, traditional home to the Dalai Lama and Namgyal Dratsang Monastery, the monastic institution associated with his early incarnations. This is perhaps the singularly most important pilgrimage site in Tibet, and rises like an enormous jewel on top of Red Mountain in the center of the Lhasa Valley. Most pilgrims spend several days visiting smaller power sites before dedicating a day to the Potala, partly out of the respect that anticipation brings, and partly to acclimatize to the altitude. The Potala has thousands of steps, and they all seem to go either straight up or straight down.

The Tibetans have their own ways of making pilgrimage. One of the favorite is called kyang chak, meaning “full stretch.” People will travel for a thousand or more miles like this to get from their homeland to Lhasa, and then continue the process as they move from one pilgrimage site to another in the valley. In this method one takes a pebble in one’s hand, turns to the direction of one’s travel, prostrates one’s body flat on the ground in that direction, stretches the pebble as far ahead as one can, drops it to the earth, and then stands up on the same place from where one had begun the prostration. One then takes two steps forward toward the pebble, bends down , picks it up, holds it to one’s heart, and repeats the process. In this way the pilgrim travels all the way from home to Lhasa and the power places there, covering the earth body-length by body-length as he or she goes. It is a slow and dusty manner of travel, yet one still sees Tibetans moving about the country this way. Westerners generally prefer bus or taxi.

The Indian Buddhist master Chandrakirti once said, “A glass of water is seen in three different ways by three different kinds of beings. Humans see it as mere water; the gods see it as ambrosial elixir; and ghosts see it as a mixture of pus and blood.” The same could be said for how different people see most Asian places of pilgrimage, and Lhasa is no exception. Although in the eyes of millions of Asians it is the holiest of cities and one of the world’s great pilgrimage sites, a less devoted visitor may be distracted by the urban chaos brought in by Communist China and its secular rule. For those with focussed vision, however, this is but a peel covering the sweet fruit of the sacred sites of the valley, and is easily bypassed.

Most Tibetans begin their pilgrimage to the city with a visit to the Jokhang, or “Temple of the Master.” This is Tibet’s first Buddhist temple, and for centuries has been regarded as the most sacred. It was built in approximately 650 AD by Songtsen Gampo, the king who first united Tibet as one country. Songtsen Gampo had five wives, all chosen for the political affiliations they would bring to his rule. Two of these were foreign, the first being a princess from Nepal and the second a princess from China. Both were Buddhist, and one of the conditions of their marriage was that King Songtsen Gampo should build each of them a Buddhist temple where they could house the monks and teachers they brought with them, and also practice their religion. The Jokhang was built for the Nepali princess. These two women and their teachers profoundly affected Songtsen Gampo. He became a Buddhist and declared Buddhism to be the national religion of his newly founded empire. Tibet remained Buddhist since that time, with the Jokhang serving as its central temple. All great Tibetan lamas since then, including the Dalai Lamas, have made pilgrimage to this temple, and many of them have taught here. In particular, since 1409 the Jokhang has served as the site of the annual Great Prayer Festival, a monumental celebration lasting for three weeks at the beginning of each new year, often attended by over 20,000 monks and tens of thousands of lay people.

Most Tibetans begin their pilgrimage to the city with a visit to the Jokhang, or “Temple of the Master.” This is Tibet’s first Buddhist temple, and for centuries has been regarded as the most sacred. It was built in approximately 650 AD by Songtsen Gampo, the king who first united Tibet as one country. Songtsen Gampo had five wives, all chosen for the political affiliations they would bring to his rule. Two of these were foreign, the first being a princess from Nepal and the second a princess from China. Both were Buddhist, and one of the conditions of their marriage was that King Songtsen Gampo should build each of them a Buddhist temple where they could house the monks and teachers they brought with them, and also practice their religion. The Jokhang was built for the Nepali princess. These two women and their teachers profoundly affected Songtsen Gampo. He became a Buddhist and declared Buddhism to be the national religion of his newly founded empire. Tibet remained Buddhist since that time, with the Jokhang serving as its central temple. All great Tibetan lamas since then, including the Dalai Lamas, have made pilgrimage to this temple, and many of them have taught here. In particular, since 1409 the Jokhang has served as the site of the annual Great Prayer Festival, a monumental celebration lasting for three weeks at the beginning of each new year, often attended by over 20,000 monks and tens of thousands of lay people.

Tibetans make their pilgrimage through the Jokhang and its dozens of chapels in the morning. Most of them carry a pot of melted butter or vegetable oil, pouring a few spoonfuls into the butterlamps on the many shrines as they make their way through the complex. Plenty of oil gets spilled on the stone floors, making the adventure a slippery one. The highlight is the main Buddha statue, an image brought to Tibet by Songtsen Gampo’s Chinese princess. Tibetans believe that this is one of the world’s oldest images of the Buddha. According to legend it was made in India shortly after the Buddha’s passing, and was taken to China during the early Buddhist movement in that country. Every Tibetan touches the crown of his or her head to its knee as they pass through the chapel in which it is housed.

Like most Tibetan temples, the Jokhang is a treasury of Tibetan art. Every wall is covered in frescos, every chapel adorned with golden statues, and every pillar bedecked with numerous scroll paintings (tangkas). It is truly a feast of the senses, with sounds of chanting monks, together with their drums, horns and bells, resounding through the corridors The aromas of incense, butter from the lamps, and campfire smoke from the clothes of the Tibetan pilgrims, all blend together to make a perfume that would cause even a Frenchman to swoon. There is a lot of pushing and pulling from the Tibetan pilgrims, who approach temple visits with great enthusiasm. The crowd slowly winds its way through the various chapels, being careful not to step on the dozens of people offering prostrations as they go.

Lhasa is also the home to several dozen monasteries. Drepung is the largest and most famous of these. Established in 1416 on the foothills to the northeast of the city, it housed 10,000 monks prior to the Communist Chinese invasion. It was the home monastery of the first five Dalai Lamas, so is especially sacred to the Tibetans. Like all Tibetan spiritual institutions, it was closed from 1959 to 1979, but with the liberalization of the 1980s was allowed to re-open its doors. Today it officially houses 300 monks, although there are usually several hundred unofficial ones also in residence. The mountains behind Drepung contain many caves where meditators over the centuries have made the traditional three year retreat.

Located in the center of the city is a nunnery called Ani Sangku, another must for every Tibetan pilgrim. Established at the mouth of a cave where a half dozen nuns achieved enlightenment in the mid-1400s, it has served Tibetan women for over five centuries and produced a steady stream of female mystics.

My personal favorite of all the Lhasa pilgrimage sites in the Lhasa Valley is the small cave and temple complex at the foot of Iron Mountain. Monks of the Dalai Lama’s private monastery, Namgyal Dratsang, did their long meditation retreats here. The caves have numerous stone images in relief on the walls; the Tibetans claim that these are rang-jung, or “spontaneously arisen.” In other words, they grew out of the walls from the flow of moisture seeping through the stone during the summer rainy seasons. The seventh century King Songtsen Gampo is also said to have made numerous winter retreats here with his two Buddhist wives.

Tibetans are a patient people. Not far from this cave site a dozen Tibetan stone carvers sit for many hours each day cutting the words of sacred scriptures into the faces of pieces of slate. Their plan is to carve out all 4,500 texts that were translated from Sanskrit into Tibetan. These slabs are being used to build a stupa, or enlightenment memorial, with the individual pieces of slate stacked on top of each other, and the text thus buried inside the walls and invisible to the unknowing pilgrim. Several hundred thousand pages of text are being carefully and painstakingly carved in this way.

After visiting these and other smaller power places in the valley, pilgrims make their way to the Potala, the place d’excellence of Lhasa, the winter residence of the Dalai Lama and his monastery, Namgtal Dratsang. Built by the Fifth Dalai Lama (but only completed after his death) on Red Mountain at the heart of the city, the Potala is one of the crowning achievements of Asia and truly one of the wonders of the spiritual world. According to legend, the mountain on which it stands hosts a cave complex in which many immortals reside, awaiting the time when they will emerge and usher in a golden age on the planet.

Like the Egyptians, the Tibetans also mummify their great spiritual leaders. The most sacred relics in the Potala are the mummified bodies of the Fifth to Thirteenth Dalai Lamas (with the exception of the Six, who died on the border of Tibet and Mongolia). In the Tibetan tradition, however, these are not simply wrapped in cloth and entombed in caskets. Rather, the body is first cleansed by passing mercury through the intestinal tract; it is then dried in salt and completely dehydrated. During this process it is kept in the seated meditation posture, and when all moisture has been removed the body is used as the central structure of a clay statue. The dehydration process causes the body to shrink considerably, but afterwards it is built up again with successive coatings of clay. The statue, which looks like a simple Buddha image, is then clothed in the robes of a monk, seated on a platform, and encased in a stupa. Pilgrims to the Potala pass by each of the eight Dalai Lama mummies, offering prayers and prostrations in front of each.

The tradition is linked to the Tantric Buddhist idea of what happens to the physical body at the time of enlightenment. Prior to enlightenment the body is just animated matter; body and mind are two different entities, with the latter departing from the former at the time of death, and moving on to the next rebirth. With enlightenment, however, the body and mind become of one nature. Therefore at death the body retains some of the qualities of the enlightened mind, even though it is no longer animated by the mind itself. A mummy of a deceased Dalai Lama therefore has the capacity to bestow the same enlightenment blessing as a living Dalai Lama. For the Tibetans today this is their most direct link to His Holiness the present Dalai Lama, for the Communist Chinese have forced him to live in exile in India since 1959, and many of his people have little hope of ever seeing him directly in person. Seeing the mummies of his previous incarnations is the next best thing.

However, the Dalai Lamas were not the only personages to be mummified in Tibet. Lama Tsongkhapa, the founder of the Gelukpa School to which all the Dalai Lamas have belonged, was mummified after his death in 1419, and thereafter all the successive lamas who ascended to his throne of spiritual leadership were similarly preserved. All ninety-six of these, however, were destroyed during the cultural revolution. From the time of the Fifth Dalai Lama, the Panchen Lama incarnations were also mummified, although these are not kept in Shigatse and not in Lhasa. Moreover, most of the Panchen mummies were destroyed by the Chinese in the 1960s. Today only the Dalai Lama mummies remain intact.

As well as the mummies of these early Dalai Lamas, the Potala contains the ornate memorial tombs, or stupas, dedicated to the specific incarnations, as well as the meditation and teaching chapels that each of them used. Again, as in the Jokhang, there is a feast of the senses, with hundreds of statues, paintings and frescos decorating the individual temples.

Only three monks from the Dalai Lama’s original Namgyal Dratsang Monastery remain in the Potala today, although ninety more monks oversee the upkeep of the shrines. Because China still has not made peace with the present Dalai Lama, who lives in India and lobbies internationally for the rights of his people, the Potala holds a strong political position in the Beijing scheme of things. Hopefully this problem will be resolved before too many more years have passed, and His Holiness will once more be allowed to return to his homeland.

In addition to these main power places in Lhasa, most pilgrims to the city make day outings to some of the hundreds of other sacred sites that lie within a few hours drive away. Perhaps the most exquisite of these is Ganden, the monastery built by Lama Tsongkhapa some forty miles to the northeast of Lhasa on the ridge of Nomad Mountain. Totally destroyed during the cultural revolution, over a dozen of the principal buildings of this illustrious hermitage have now been restored. Another popular destination is Tsurpu, the home of the Karmapa lamas, also only a couple of hours drive. Tsurpu was also totally ravished by the Communists, but has been recently restored. The cave complex at Drak Yerpa also ranks high on the list for Tibetans, for it has been used for long meditation retreats for centuries now by many of Tibet’s most famous mystics. Each of these power sites has a thousand stories and legends associated with it. The casual pilgrim can only hope to scratch the surface.

Nonetheless the Tibetans believe that anyone who makes pilgrimage to the sacred Lhasa Valley and the many power places associated with it enters into a sphere wherein historical or spiritual knowledge become peripheral to the experience. Merely being there in a clear and positive mindframe spontaneously awakens the karmic seeds of 10,000 past lives, and gives rise to an unheralded wave of transformative energy. This brings great benefit in this lifetime, is further activated at the time of death, and is carried far into the future, where it continues to work its sublime magic.

The Dalai Lama has now lived in exile for forty years, and is not permitted even to visit the place of his birth. The Tibetans feel this loss deeply, for to them he symbolizes everything dear to them as a people, both culturally and spiritually. Wherever one goes one is asked for photographs of him; but even these are banned by the Communists, and both the giver and the recipient can be jailed. For the Tibetans, a pilgrimage to Lhasa and its sacred power places is the closest they can get to a meeting with His Holiness.

They also believe that the positive energy generated by making pilgrimage to the Lhasa sites associated with the Dalai Lama and his early incarnations is the strongest contribution they can make toward a resolution of the Tibet/China conflict, and his eventual safe return. His Holiness has demanded a non-violent approach to the conflict; they regard pilgrimage as a method of generating the good karma that can work in ways beyond the comprehension of the communists. Chairman Mao said, “Power comes from the barrel of a gun.” Tibetans believe that all good things comes from the source of spiritual energy, and that one of the ways of generating this energy is the good karma created by undertaking pilgrimage.

They rejoice and draw even deeper inspiration when they see Westerners making this same pilgrimage. To the Tibetans, the Chinese invasion of Tibet was a result of the general lack of merit of all peoples in the world, a bad karma that they had to take upon themselves in order to diffuse and absorb the negative energy of the planet. The remedy can only be found in the increase of the planet’s positive energy. One of the principal means whereby this is affected is pilgrimage to the power places. When the world’s positive energy or “good karma” has been sufficiently increased, the chains of Chinese Communist rule over Tibet will be relaxed, and Tibet will once again be allowed to serve as a spiritual center to the planet.

In 1979 the Dalai Lama received a visit from Grandfather David, the grand elder of the Hopi Indians. Grandfather David expressed his belief that the Hopi are the peacekeepers of the Western hemisphere, and the Tibetans of the eastern. The two are spiritual brothers, and together have the responsibility of guiding humanity through the present very fragile phase of its history. His Holiness and Grandfather David meditated and prayed together for world peace. A few months later liberalization swept across China, and the mantle of iron rule was lifted in Tibet. The monasteries and temples in Tibet were again allowed to re-open and re-build.

This, according to Grandfather David, was a sign that the planet had now passed through its darkest and most dangerous period, and was on the path to healing. This healing process would take time and consistent effort, but was like a strong plant that was on the path of growth, and only needed to be tended in order to mature and produce a crop of great benefit.

In 1989 His Holiness received the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to show the world how conflicts can be resolved without hatred or violence. In 1979, the same year he had met Grandfather David, His Holiness also made a teaching tour through the Soviet Union. In 1989 Russia dropped it’s policies of militant rule, and the Cold War unexpectedly came to an abrupt end.

Thus it seems that the prophecy of Grandfather David is finding its fulfillment, even in our generation.

About the author:

Glenn H. Mullin spent twelve years studying Tibetan Buddhism in the Himalayas of India. He has over a dozen books in print, including Mystical Verses of a Mad Dalai Lama (Quest Books), Tsongkhapa’s Six Yogas of Naropa (Snow Lion Publications) and Living in the Face of Death (Snow Lion Publications). He has work as script consultant on three Tibet-related documentary films and as special advisor on four television productions, and has co-produced four CDs of Tibetan sacred music. Glenn leads tours for Runaway Journeys.

This article was originally published in the June/July 1998 issue of Power Trips magazine.