70 First Nations medicine wheels are known to exist on the plains of North America, and more than half of them are in Alberta, Canada

By Mary Johnson

It sounded simple: just turn south onto Secondary Road #847 at Bassano and drive toward the Bow River for 15 kilometers. We honestly didn’t think the Majorville Medicine Wheel would be that hard to find, even without explicit directions. For one thing, it was almost certainly on the highest hill around. Also, since it was the second best example of an ancient medicine wheel in North America, surely the locals would be able to point us in the right direction. It sounded like just the perfect way to spend a summer afternoon in Alberta, Canada. Most important, it sounded like a power place. In her book Western Journeys: Discovering the Secrets of the Land, Beverly Sinclair described her experience approaching a medicine wheel: “…as though the ghosts of buffalo hunters are watching me.” She said she felt “strangely moved by the hilltop’s mystery.”

After several hot, dusty and totally confused hours of hiking across prairie, surprising cows and alarming gophers, we had to give up and go home. The first lesson in looking for archaeological sites seems to be to get directions from someone who knows what they are talking about!

Original purpose now lost

I didn’t know much about medicine wheels when I started and even less after doing some research. Do medicine wheels in today’s culture now embody something totally different from the original concept? Since the coming of Europeans to North America, the exact knowledge and purpose of medicine wheels has been lost. The term has come to mean many things to many people, and has taken on New Age concepts like astrology, earth and environmental beliefs, dream work, and spiritual awakening. Now it is embedded in pop culture the say way that “sit-ins” used to be part of the ‘60s. In some national parks, the rangers spend a lot of their time dismantling hikers’ medicine wheels and returning the land to its natural state. Native Americans (like the popular author Sun Bear) have rooted a whole system of belief and behavior in the medicine wheel.

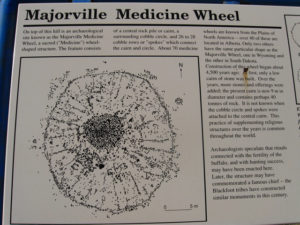

The ancient medicine wheel does not have any “right” construction, but archaeologists have classified roughly eight types and consider it necessary to have at least two of the following three traits: a central stone cairn, one or more concentric stone circles, and two or more stone lines radiating outward from a central point. Some of the sites may have been burial mounds of a revered chief or warrior. Blood Indians of southern Alberta have build modern wheels to commemorate ancestors; a long-standing tradition for possibly thousands of years.

Ancient astronomical uses?

It I widely believed that one function of medicine wheels was astronomical. Medicine wheels are always located on the top of the highest hill in a given area and have a clear view of all four directions. One astronomer we spoke to (David Vogt of Vancouver) examined the hypothesis in the past and says that although there is some stone evidence of astronomical alignment, it cannot be proven in fact. After studying the Majorville and Big Horn wheels, he says they are still completely mysterious and could have had many purposes; from vision quests and sundances to alien landing sites.

One of the more likely scenarios is that medicine wheels were an important part of Native American ritual. One of the rocks frequently found at medicine wheels were called “iniskim” by the Siksika (previously known as Blackfoot) and were “buffalo calling rocks.” These were powerful totems. Buffalo provided everything these people needed to survive the frequently harsh environment of the plains. Both Piegan and Siksika legends tell of the first iniskim being discovered by a woman when it “sang” to her of its magical powers. It is certain that these were important in hunting and buffalo fertility rituals.

Still used by first nations

We spoke to Floria Duck Chief in the Siksika cultural office, who had gone to the Majorville wheel with two tribal elders. At the base of the hill, they prayed to the four directions and left tobacco in four directions before they climbed up to the wheel. Once at the top, they prayed again before going into the circle, approaching it from the north and coming into the circle facing the south. Floria also remembered that, when she was very young, her grandmother showed her an iniskim rock she kept in a pouch, saying it protected her. It had been painted – rubbed with red ochre.

Weeks after my first attempt to find the Majorville wheel, I got lucky and found a retired archaeologist (Barney Reeves) who has been roaming the Alberta prairies for 40 years, and who, coincidentally, happened to know my father from their university says. Barney told us the “legal” description of the site along with some very helpful directions. Armed with a topographical map showing townships and ranges, we again set off. With only a few wrong turns, we finally arrived at the bottom of the Majorville Medicine Wheel hill.

Majorville Medicine Wheel

This time, although we drove straight there from Calgary, it took us a good two hours. Four-wheel drive would have been helpful but not absolutely necessary. We took Highway #1 (the Trans Canada) going east from Calgary, and then turned sough on Highway #24 at Vulcan (a tiny farming community which has a model of the Starship Enterprise at the town centre). Then we took #534 east to Lomond, where we turned north on /secondary Road 845. Then we turned east onto Secondary Road 539 and drove for about 16 km. We then turned north onto a rough section of road (exactly 5 km from the Badger Lake turnoff) and followed that for about 18 km.

This is a rough road that you share with cows, and it’s important to go very slowly. After about 15 km there is a Y in the road, where you must bear to the left. There is a cattle guard (Texas gate) and the medicine wheel hill is about 3 km farther. There is a sign at the bottom of the fenced hill so you know you have arrived. It was extremely windy that day; although it was far too hot to wear my coat, I had to use its detachable hood for ear protection from the 60 km/h gusts. Fortunately there were only cows to witness this fashion faux pas.

This is a rough road that you share with cows, and it’s important to go very slowly. After about 15 km there is a Y in the road, where you must bear to the left. There is a cattle guard (Texas gate) and the medicine wheel hill is about 3 km farther. There is a sign at the bottom of the fenced hill so you know you have arrived. It was extremely windy that day; although it was far too hot to wear my coat, I had to use its detachable hood for ear protection from the 60 km/h gusts. Fortunately there were only cows to witness this fashion faux pas.

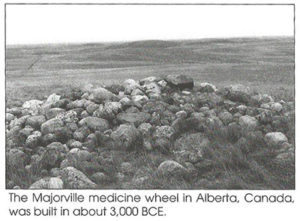

As I approached the wheel, I was surprised at the size of it. It has a central cairn about nine meters across, surrounded by a stone circle. About 28 spokes link the central cairn and circle. All in all it was about 30 meters across. The thing that made me catch my breath, however, was not the construction or the stones, but what was left among the stones.

There were offerings of braided rope (it looked like cedar bark), ears of corn and feathers tied to rocks and sticks with red material. It looked as though it might have done a thousand years ago when the Caucasian invasion was yet undreamed of. I looked around me and saw prairie as far as the eye count see. The Bow River gorge was less than a kilometre away. I felt sincere awe and an appreciation of the lives of the people who build the wheel.

As old as Stonehenge

The wheel had been partly excavated (and then restored) by archaeologists in 1971. Artifacts were found that dated the wheel to 3,000 BCE. This is only 500 years after construction was started on Stonehenge, at that point in human history, time spans of 500 years are really no time at all. Were these “simultaneous inventions” just coincidental, or did some yet-undiscovered force influence them both?

The really interesting thing to me was that there appears to be a period of time, between 2,000 and 3,000 years ago, when the wheel was not in use. What happened? Was there a plague, a revolution, a crisis? More importantly, what motivated its re-use? Was the knowledge of the wheel’s existence and purpose forgotten and rediscovered, or was it held and passed on through the millennia?

The wild Alberta prairies

Although I now live on the West coast (and consider it home), there is a real danger when I get back onto prairie soil. Not only did I grow up in Alberta, but it is also the place of my ancestry for many generations. So when my feet get on prairie grass, they start trying to grow roots and stay. It is like feeling you can stretch your arms and encompass the earth, even though the sky is so wide it seems endless.

Although I now live on the West coast (and consider it home), there is a real danger when I get back onto prairie soil. Not only did I grow up in Alberta, but it is also the place of my ancestry for many generations. So when my feet get on prairie grass, they start trying to grow roots and stay. It is like feeling you can stretch your arms and encompass the earth, even though the sky is so wide it seems endless.

On a beautiful day on the prairie it is impossible to realize that this can be some of the most inhospitable land on the planet for humans to dwell. In the winter, the wind screams across the hills, freezing everything in its path, and the temperature will be –40 for weeks on end. I found it hard to imagine anyone being on the top of this hill in the dead of winter. I’m sure gatherings were probably regular and seasonal, but probably not in the colder months.

The site is vulnerable

I have a real sense of trepidation in telling other people about the wheel. It is a place that has a huge sense of ritual and being, but there aren’t busloads of tourists driving by. In fact, to get to the wheel you have to be quite determined and armed with maps. A sense of adventure wouldn’t go amiss. The site is unguarded and vulnerable to vandalism and souvenir hunters. My fear stems from what happened to the Big Horn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming. Since its discovery in the late 1800s, it has been plundered and radically altered from its original state’ so much so that a number of groups including the Medicine Wheel Alliance, the Big Horn National Forest, and the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office signed an agreement in 1933 limiting access. It’s not surprising those steps took place considering that each year over 70,000 people visit between July and November.

Bad karma from stealing stones

To anyone contemplating taking home a “souvenir” from a medicine wheel, I offer a warning: one couple from Philadelphia who visited the Big Horn wheel stole one of its rocks. A series of such bad experiences befell them that they had to mail the rock back. This is not an isolated incident. In the book In the Ring of Fire (Mercury House, 1997) James Houston reports that an average of ten people per week mail rocks back that they had stolen from Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. It is taboo to remove even a tiny stone from the home of Pele, the goddess of fire. Letters accompanying the returned rocks contain long lists of misfortunes that haunted tourists who ignored the warnings. The law of karma is indeed real. What goes around comes around. It’s that circle thing.

Please do not leave offerings

One final thought about leaving offerings at sacred places. It has become a very serious problem, especially in England, where a group Save Our Sacred Sites, has been formed to protect ancient monuments. They advise it is not necessary to show your respect for a site by lighting candles or incense, leaving flowers, grain, salt or anything.

Adding crystals to “re-harmonize” ancient stones is not only arrogant but potentially harmful to the energies at a site. So, even if First Nations people leave sweetgrass, tobacco or feathers at a medicine wheel, that doesn’t mean you should. You can show your respect through your attitude and your behaviour. You can clean up litter left by less respectful visitors. You can also talk to others about the need to preserve and protect ancient sacred sites.

The Boscawen’un stones in Cornwall have recently been seriously damaged and may soon be fenced off and as inaccessible as Stonehenge has become. We are fortunate that the Majorville Medicine Wheel is now freely accessible to us all. Let’s hope it can stay both safe and free for future generations to experience its power and ponder its mysteries.

This article was first published in the December/January 1998 issue of Power Trips magazine.