by Michael Berman

Though hard to believe as you walk down Kilburn High Road today, (in the suburb of London where I have spent most of my life) back in the 18th century taking the local medicinal waterous used to be a highly popular pastime and attracted many people to the neighbourhood.

Kilburn grew up on the banks of a stream which has been known variously as Cuneburna, Kelebourne and Cyebourne, which flows from Hampstead down through Hyde Park and into the River Thames. It is suggested the name means either Royal River or Cattle River (‘Bourne’ being an Anglo-Saxon word for ‘river’). The river is known today as the River Westbourne. From the 1850s it was piped underground and is now one of London’s many underground rivers.

The name Kilburn was first recorded in 1134 as Cuneburna, referring to a priory which had been built on the site of the cell of a hermit known as Godwyn. Godwyn had built his hermitage by the Kilburn river during the reign of Henry I, and both his hermitage and the priory took their name from the river. Kilburn Priory was a community of Augustinian canonesses. It was founded in 1134 at the Kilburn river crossing on Watling Street (the modern-day junction of Kilburn High Road and Belsize Road). Kilburn Priory’s position on Watling Street meant that it became a popular resting point for pilgrims heading for the shrines at St Albans and Willesden. The Priory was dissolved in 1536 by Henry VIII, and nothing remains of it today.

The priory lands included a mansion and a hostium (a guesthouse), which may have been the origin of the Red Lion pub, thought to have been founded in 1444. Opposite, the Bell Inn was opened around 1600, on the site of the old mansion.

The fashion for taking ‘medicinal waters’ in the 18th century came to Kilburn when a well of chalybeate waters (water impregnated with iron) was discovered near the Bell Inn in 1714. In an attempt to compete with the nearby Hampstead Well, gardens and a ‘great room’ were opened to promote the well, and its waters were promoted in journals of the day as cure for ‘stomach ailments’:

Kilburn Wells, near Paddington.-The waters are now in the utmost perfection; the gardens enlarged and greatly improved; the house and offices re-painted and beautified in the most elegant manner. The whole is now open for the reception of the public, the great room being particularly adapted to the use and amusement of the politest companies. Fit either for music, dancing, or entertainments. This happy spot is equally celebrated for its rural situation, extensive prospects, and the acknowledged efficacy of its waters; is most delightfully situated on the site of the once famous Abbey of Kilburn, on the Edgware Road, at an easy distance, being but a morning’s walk, from the metropolis, two miles from Oxford Street; the footway from the Mary-bone across the fields still nearer. A plentiful larder is always provided, together with the best of wines and other liquors. Breakfasting and hot loaves. A printed account of the waters, as drawn up by an eminent physician, is given gratis at the Wells. ”

-The Public Advertiser, July 17 1773.

In the 19th century the wells declined, but the Kilburn Wells remained popular as a tea garden. The Bell was demolished and rebuilt in 1863, the building which stands there today.

The following information on the waters was found in The Domestic Encyclopaedia Vol 4 by A. F. M. Willich, which was published in 1802:

Kilburn-Water, is a saline mineral fluid, obtained from a spring at Kilburn-well, about two miles from the end of Oxford-street, London. This water was formerly in great repute, but is at present seldom employed. Nevertheless, it promises to be serviceable in cases of habitual costiveness, where powerful laxatives would be productive of dangerous consequences ; as it may be used with safety, till the intestines have recovered their natural tone. It may farther be advantageously taken by persons of sedentary lives, who are peculiarly subject to hypochondriasis, indigestion, and other disorders arising from relaxed habits. The dose is from one to three pints, which should be drunk at short intervals, till it produce a purgative effect : and, as its operation is very slow, it appears to be eminently calculated for persons, whose stomachs are delicate or impaired.

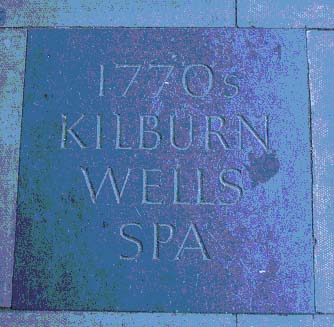

The only evidence that remains today of the existence of the former Wells is a commemorative paving stone, on the corner of Belsize Road and Kilburn High Road.

The following extract from Edward Walford’s 1878 publication Old and New London: Volume 5. throws further light on what the neighbourhood used to be like. It also shows how complaints about the frightening pace of change in the modern world are actually nothing new, for people were making them in the last century too:

The following extract from Edward Walford’s 1878 publication Old and New London: Volume 5. throws further light on what the neighbourhood used to be like. It also shows how complaints about the frightening pace of change in the modern world are actually nothing new, for people were making them in the last century too:

… Such has been the growth of London in this north-westerly direction, within the last half-century, … and such the progress of bricks and mortar in swallowing up all that was once green and sylvan in this quiet suburb of the metropolis, that the “village of Kilburn,” which within the last fifty years was still famous for its tea-gardens and its mineral spring, has almost become completely absorbed into that vast and “still increasing” City, and in a very short space of time all its old landmarks will have been swept away.

… Kilbourne … took its name from the little “bourne,” or brook, … rising on the southern slope of the Hampstead uplands. It found its way from the slope of West End, Hampstead, towards Bayswater, and thence passing under the Uxbridge Road, fed the Serpentine in Hyde Park. The brook, however, has long since disappeared from view, having been arched over, and made to do duty as a sewer.

… before the end of the sixteenth century, and even perhaps earlier, near a mineral spring … there arose a rural house, known to the holiday folks of London as the “Kilburn Wells.” The well is still to be seen adjoining a cottage at the corner of the Station Road, on some premises belonging to the London and North-Western Railway. The water rises about twelve feet below the surface, and is enclosed in a brick reservoir of about five feet in diameter, surmounted by a cupola. The key-stone of the arch over the doorway bears the date 1714. The water collected in this reservoir is usually about five or six feet in depth, though in a dry summer it is shallower; and it is said that its purgative qualities are increased as its bulk diminishes. These wells, in fact, were once famous for their saline and purgative waters. A writer in the Kilburn Almanack observes:-“Upon a recent visit we found about five feet six inches of water in the well, and the water very clear and bright, with little or no sediment at the bottom; probably the water has been as high as it now is ever since the roadway parted it from the ‘Bell’ Tea Gardens, not having been so much used lately as of old.” “Is it not strange,” asks Mr. W. Harrison Ainsworth, “that, in these water-drinking times, the wells of Hampstead and Kilburn should not come again into vogue?”

From: ‘Kilburn and St John’s Wood’, Old and New London: Volume 5 (1878), pp. 243-253. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45234 [accessed: 02 September 2009].

Unfortunately, however, the wells never did. And these days, as you struggle to make your way through crowds of shoppers heading for Sainsbury’s, Primark, Poundland and the like, it is hard to imagine they ever even existed. What you can do, though, is to drown your sorrows at the passing of an era in the rebuilt Old Bell (pictured below).

Well dressing is the art of decorating (dressing) wells, springs or other water sources with pictures made of growing things. This ancient custom, still popular all over Derbyshire, is thought to date back to the Celts or even earlier. The church banned it as water worship, but the tradition refused to die. The wells are dressed with large framed panels decorated with elaborate mosaic-like pictures made of flower petals, seeds, grasses, leaves, tree bark, berries and moss. Wooden trays are covered with clay, mixed with water and salt. A design is drawn and its outline pricked out onto the surface of the clay. The design is then filled in with natural materials, predominantly flower petals and mosses, but also beans, seeds and small cones. Well-dressings are beautiful and delicate and take a lot of work to make, and yet they only last for a few days. After the well dressing is erected next to the well it is blessed in a short outdoor service. In towns and villages that have several wells, a short procession from well to well is carried out during the blessing of the wells. The well dressing season spans from May through to late September. And, who knows? Perhaps there was a time when the Kilburn Wells were dressed in this manner too.

About the author:

Michael Berman BA, MPhil, PhD, works as a teacher and a writer. Publications include The Power of Metaphor for Crown House, and The Nature of Shamanism and the Shamanic Story for Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Shamanic Journeys through Daghestan and Shamanic Journeys through the Caucasus are both due to be published in paperback by O-Books in 2009. A resource book for teachers on storytelling, In a Faraway Land, will be coming out in 2010.

As for his work in the field of religious studies, although Michael originally trained as a Core Shamanic Counsellor with the Scandinavian

Centre for Shamanic Studies under Jonathan Horwitz, these days his focus is more on the academic side of shamanism, with a particular interest in the folktales with shamanic themes told by and collected from the peoples of the Caucasus. For more information please visit

www.Thestoryteller.org.uk