Southwest Wales, source of the great Stonehenge bluestones, is rich with prehistoric monuments

by Lise Hull

A glance at the Ordnance Survey (OS) map of West Wales reveals an incredible density of prehistoric monuments in Pembrokeshire, including cromlechau, standing stones, cairns, tumuli, and stone rows. Interestingly, only a few stone circles exist. Standing in quiet solitude before these mysterious monuments, I am always struck by a gut level awareness, the recognition of a physical connection that transcends time and place. It’s a startling but exhilarating sensation that the energy radiating from these sites is real. This strange energy even has the ability to alter compass directions, as my husband and I found out while exploring the cairns on top of Plumstone Mountain one stormy afternoon!

A glance at the Ordnance Survey (OS) map of West Wales reveals an incredible density of prehistoric monuments in Pembrokeshire, including cromlechau, standing stones, cairns, tumuli, and stone rows. Interestingly, only a few stone circles exist. Standing in quiet solitude before these mysterious monuments, I am always struck by a gut level awareness, the recognition of a physical connection that transcends time and place. It’s a startling but exhilarating sensation that the energy radiating from these sites is real. This strange energy even has the ability to alter compass directions, as my husband and I found out while exploring the cairns on top of Plumstone Mountain one stormy afternoon!

Every time I approach one of West Wales’s ancient monuments, I discover more than a stone formation that has persevered despite the effects of time, nature and human intrusion. I feel the energy that vibrates from the stones. I experience a spiritual connection that transcends rationality and common sense. I experience scenic drama, a sense of place and the reality of the moment. I believe the stones have an ancient wisdom that can be tapped, if we are open to the possibility.

Over the years since my first encounter with the ancient stones of Pembrokeshire, I have learned that an abiding connection exists between the stones, the land and the people who so deliberately placed them on the windswept moorlands and craggy ridges. And, I have realized a profound spiritual bond of my own with the land, the stones and the energy left behind when the ancients of Pembrokeshire passed through time. My initial introduction to Britain’s ancient monuments was a visit to Pentre Ifan, the best known and most photographed of Wales’ prehistoric sites. Little did I know how dramatically my life would be impacted by the experience.

Pentre Ifan, with its wedge-shaped capstone pointing almost due north and poised precariously on the tips of three upright slabs, stakes a commanding presence on the grassy hillside bordering rugged Mynydd Preseli, otherwise known as the Preseli Mountains. Though no longer covered by its enormous earthen mound, the chambered tomb is well preserved. My first impression of Pentre Ifan was as a total novice who had no knowledge that this strange, angular figure had once been the heart of a complex structure. What I saw was a solitary form dominating its surroundings, pridefully displaying its state of near perfection. Pentre Ifan sparked a passion to discover more.

Although the cromlech is well known, Pentre Ifan is by far not the only impressive stone monument marking the ancient Welsh landscape. Indeed, after returning to Pentre Ifan several times, I have noticed that, for some reason, Pentre Ifan seems almost devoid of energy. At times it seems an inert formation of stone unlike its vibrant cousins scattered elsewhere in the Preselis. Perhaps, the chamber’s popularity with tourists has altered the atmosphere. The stillness is almost palpable.

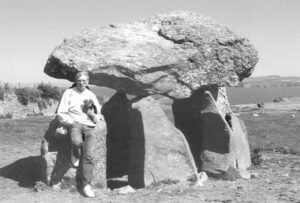

Travel guidebooks for Pembrokeshire highlight the most accessible stone monuments and are fine starting points for locating sites like Pentre Ifan. Carreg Samson, another cromlech often mentioned in guides to Pembrokeshire, rises like a mammoth beacon from a mucky field at Longhouse Farm, just northeast of St. David’s. Named for a Celtic saint, the cromlech supposedly thudded onto the spot with a flick of Samson’s little finger! Though used earlier this century as a sheep shelter, the chamber is in solid condition, the fat capstone resting on three of seven uprights, defying the farmers to pull it down.

Tractors rumble close by, sheep and cattle wander the field, and Carreg Samson withstands all the bother. In the distance, the breathtaking beauty of the sea startles the senses and has caused me to wonder about the people who erected the massive stones with such precision. Were they as entranced with the view, then certainly even more brilliant without the farm and hedgerows to block the way? Were they too distracted by their grief to notice? Did they choose this particular spot for their dead because of the energy they felt here? Sadly, I can only imagine the labors and the behaviors of the ancients, and a site like Carreg Samson seems to encourage such musings.

Discovering Cerrig y Gof

While guidebooks are suitable for a quick tour of the Welsh countryside, OS Maps are the megalith hunter’s greatest resource. Using the maps, I found myself exploring places in Pembrokeshire I would otherwise have never seen. Thanks to my trusty maps, which are available in almost every bookstore or stationary shop, I experienced Wales’ ancient energy. One of my favorite discoveries is Cerrig y Gof, the so-called “smith’s stone” burial site which sits close to the A487 roadway leading into Newport. The site is clearly marked on the OS map, so I was fairly certain it would be easy to locate. But, after making several passes along the length of road where I thought the map directed me, I admitted defeat and began toward home. In a flash, my peripheral vision caught a fleeting glimpse of something gray in the green field. My gut knew we had found the site. Abruptly turning back toward Newport, my husband, Marvin, parked the car mere inches from the edge of the road. Out we leapt toward the goal.

Camouflaged behind a thick hedgerow sat Cerrig y Gof. Finding no one at home when we sought permission to trudge through the field, Marvin and I cautiously unlatched the metal gate into the pasture, pausing to close it securely. Not too far ahead lay a jumble of stones I immediately identified as Cerrig y Gof (of course, it was the only monument in the field!). The round cairn is an anomaly in this area, its five chambers in varying stages of ruin. Of the four surviving capstones, only one still covers its chamber. The stones drew me to them as if trying to relate their past. I had difficulty hearing their message and felt humbled in their shadow.

Like Pentre Ifan, which is only a few miles away, Cerrig y Gof sits at the northern edge of the desolate expanses of the Preseli Mountains. Just across the A487 from the field, the land starts to rise, jagged outcrops protruding randomly into the barely inhabited landscape. That is to say, barely inhabited by humans but filled with ancient stone cairns, standing stones, hut circles and prehistoric stone quarries.

Source of Stonehenge bluestones

Deciding to venture on foot into the Preselis, I grabbed my OS maps and charted our next destination. One area caught my attention. It was filled with ancient sites, including Foel Drygarn and Carn Meini, the possible quarry site for the bluestones of Stonehenge. What made the location even more attractive was the adjacent public footpath, which offered a reasonable hike and easy access from Crymych, a village bisected by the A478 at the eastern edge of the Preselis. When I chose this hike, I had no idea that I would encounter one of Pembrokeshire’s most precious and most invigorating spots.

The day Marvin and I walked to Carn Meini was unusually warm and sunny, normally blessings in the oft cloudy, oft wet climate of West Wales. For me, a bit out of shape and a bit susceptible to overheating, the climb to Foel Drygarn at times seemed insurmountable. Thankfully, I had my walking stick to haul me up when my endurance failed! When I reached the hilltop, I was rewarded with a sense of accomplishment and the panorama of Mynydd Preseli. All around, the sweeping landscape teems with gray stones, some natural, others transported by the ancients. The drama of the craggy terrain was intensified by the presence of the ancient sites. To reach the top of Foel Drygarn, we had already clambered through hut circles and walled enclosures. The mere recognition of these relics encouraged us upward to the apex of the ridge.

The name, Foel Drygarn, comes from three Bronze Age cairns that sit at the ridgetop, said to mark the burials of three kings, Mon, Maelen and Madog. Though the kings have disappeared, the cairns remain an incredible sight. Piles of stone, somewhat scattered but distinctly grouped into three separate mounds, identify the burials. I found them fascinating, and had difficulty keeping my foothold while I explored as much as possible. The gentle breeze prepared me for the next leg of the hike, which took us past a small forested area and onward to Carn Ferched, Carn Gyfrwy and, finally, to Carn Meini.

Each cairn had its own peculiarities and at least one supported a makeshift sheep shelter. We agreed that the shelter would have been adequate protection if we met up with a sudden storm or heavy fog, common in these parts. We passed other cairns as we made our way to Carn Meini. Abruptly, there we were, standing at the spot where the bluestones began their journey to Salisbury Plain! The stark landscape isolated us from the rest of humanity as it must have isolated the prehistoric people who dwelled close by. The bland gray and tan rock seemed foreboding, and I walked about in a daze, trying to absorb as much as possible, knowing one long look would never suffice. The stones will endure long after I have passed by, but in that moment, I knew I had once again connected with the ancients.

Repeatedly when I encounter ancient stone monuments, I feel such a connection. It’s not a rational sensation, but something from within. It may be instinctive, harkening back to our animal origins. The feeling is something for me that pulls me back to Pembrokeshire as often as possible. Even if I cannot be there physically, I feel the bond when I remember the stones.

Vibrant Llech y Drybedd

Later, hungrily studying my OS maps for more ancient stones, I noticed a burial site named Llech y Drybedd. Soon, I found myself in the midst of the ancient Welsh countryside, this time north east of Newport and the Preselis, close to the village called Moylgrove. The trip started ominously, threatening rain and already windy. Finally, we reached a dead end, a road that seemed to vanish. According to the map we had arrived, yet the burial chamber was nowhere in sight. The tempest was almost upon us, and we had a decision to make – turn back without finding this clearly marked site, or brave the omens and take a chance that the map would not disappoint us. The tiny dot where Llech y Drybedd supposedly stood seemed next to an almost undetectable jog in the lane, marked on the map with a footpath. We trusted the map, walked briskly down the lane, and, a few yards from the car, found a stile.

Secluded behind the rocky hedge stood Llech y Drybedd, alone and burdened by the rain. As I stood on the rungs of the stile, a strong gust forced me backward and I almost fell. But, with my goal in sight, I refused to give in to that swirling gale. In some ways, the cromlech resembles Carreg Samson, both consisting of an enormous capstone perched on three squat uprights and both tossed into place by that energetic St. Samson. Yet, Llech y Drybedd’s remote setting and the gloom of the day heightened my sensory experience, my awareness of the power of the site. The stones of Llech y Drybedd emanated a vibrancy that is difficult to comprehend but unmistakable on a gut level.

Enormous Garne Turne

Garne Turne emits a sensation similar to what I experienced at Llech y Drybedd. The burial chamber must have been an incredible sight in the days before the mammoth capstone slumped, its weight compressing the stubby uprights that bore the burden. Located near Wolfscastle at the western edge of Mynydd Preseli, the long cairn still fascinates, because of its enormity and its rugged setting in a field of rocky moorland. The brisk winds and rains that pummelled the spot on the typical fall day when I visited Garne Turne created the ideal atmosphere for a trek into the Pembrokeshire moorlands. Though the walk was short, the scattering of rocks forced us to pick our steps carefully, pushing through occasional patches of bracken.

I had again stumbled on a place with an eerie quality. I sensed that something beyond my comprehension had happened there. That consciousness of the unknown piqued my curiosity and drew me into the site. At first glance, the collapsed burial chamber looks like the other natural stone piles in the area, especially those protruding further on. My perspective shifted when, as I approached the chamber, I identified a standing stone keeping watch, signaling the ancient significance of the place. I felt the spirit of the ancients. I also felt fear, partly due to the dreary weather, the unfamiliarity of the location, and the attitude of the stones. But, my fear was tempered by an abiding respect and an appreciation for what I could never discover – why the ancients revered this place.

The ancient stones of Pembrokeshire stir something instinctive inside of me. I recognize the feeling, sense the energy of the stones, and, consequently, feel just a bit deprived because there is no written record (at least one we can decipher) for us to bridge the centuries. Perhaps the stones are portals to the past, doorways through which we cannot pass despite our modern technology. Still, we can sense the presence of the people who walked where we now step. Sometimes, I long to experience that past, to gain insight and understand the full significance of the stones. Perhaps, the ancients felt as I do, recognizing the sensation but not fully comprehending its meaning. Perhaps, that’s the real bond we share.

For me, Pembrokeshire’s prehistoric monuments stimulate a deep awareness of the unknown, an appreciation for the world around me, and the thirst to live as fully in the moment as possible. In time, the stones will share their secrets with me.

About the author:

Lise Hull is a recognized authority on British castles and heritage, with a Master of Arts degree in Heritage Studies from the University of Wales, Aberystwyth, as well as a Master of Public Affairs degree, specializing in Historic Preservation, from Indiana University. She is the author of several of books on Britain, including Britain’s Medieval Castles (Praeger: 2005), The Great Castles of Britain & Ireland (New Holland: 2005) and Castles and Bishops Palaces of Pembrokeshire (Logaston Press, 2005). She has also penned numerous articles for magazines and websites on British heritage sites and is a regular contributor to Faerie Magazine. Visit her websites at www.lisehull.com and www.castles-of-britain.com.

This article was originally published in the December/January 1999 issue of Power Trips magazine, and is re-printed with permission from the author.