For centuries, miraculous cures have been attributed to the land where a chapel now stands

by Robert Scheer

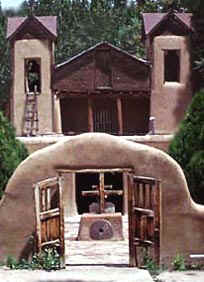

Thirty miles north of Santa Fe, New Mexico, on a hill near the Santa Cruz river, stands El Santuario (The Shrine) of Chimayó. This adobe church was designated as a “National Historic Landmark” in 1970 by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Thirty miles north of Santa Fe, New Mexico, on a hill near the Santa Cruz river, stands El Santuario (The Shrine) of Chimayó. This adobe church was designated as a “National Historic Landmark” in 1970 by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Originally a private chapel, constructed from 1814 to 1816, it was bought by a private group in 1929 and turned over to the Archdiocese of Santa Fe.

There are conflicting stories about how the chapel came to be built here.

The official brochure of El Santuario de Chimayó repeats what is described as a “tradition passed from one generation to another” by the local people, although they acknowledge there is no written testimony to support the story.

According to this legend, on Good Friday in 1910, Don Bernardo Abeyta, of the Hermandad de Nuestro Padre Jesus el Nazareno (Penitentes), saw a strange light emanating from one of the hills near the Santa Cruz river, at Chimayó. Going to the spot, Don Bernardo started digging with his bare hands into the earth, where he found a crucifix. He supposedly left the crucifix there, went to the village, told his neighbors, and brought them back to witness his discovery.

They called the priest, Fr. Sebastian Alvarez, who organized a ceremonial procession to carry the crucifix back to the church in Santa Cruz, where it was ensconced in the main altar. But, the next morning, the crucifix was gone. Miraculously, it was found to have returned to the Chimayó hillside where it had been first discovered. When the same thing happened, after a second and third procession to bring the “miraculous” crucifix back to the church, in Santa Cruz, it was decided to leave the crucifix in Chimayó and build a small chapel over it.

A much different legend is told by Chris Morton and Ceri Louise Thomas in The Mystery of the Crystal Skulls. They were given a tour of El Santuario by Jamie Sams, a Santa Fe author who says that, in a previous incarnation, she was apprentice to a Mexican shaman. Morton and Thomas report that Sams told them the local Pueblo people had been forced by a wealthy landowner to build the sandstone church over a site which was already sacred to them. Sams said it was common for “early Christian settlers to build their churches right on top of the indigenous people’s sacred sites.”

Regardless of how the chapel came to be, most visitors don’t come to admire the old building. Instead, they seek miraculous cures. Even the chapel’s official brochure recognizes that Chimayó was famous for its healing powers before the chapel was built. A letter written by Fr. Sebastian Alvarez to the Episcopal See of Durango in 1813 (one year before work started on the building) speaks of people “coming from afar to seek cures for their ailments, and the spreading of the fame of their cures induced many more faithful to come in pilgrimage.”

A small room at the back of the chapel is called El Pocito. It is also known as the “Room of Miracles.” There is a round hole in the floor, through which people scoop out some of the sand. Some kneel and kiss the earth; some rub it on their bodies or onto photographs of family members too ill to travel. Most people carry home a small bagful. Some even eat a little of the sand.

It is not uncommon for 2,000 pilgrims to congregate here on Good Friday. El Santuario attracts nearly 300,000 visitors each year.

Search for Hotels Near Santa Fe, NM

On the walls of the medicinal sand room are hundreds of letters and photographs from visitors thankful for the healing they say they received here.

El Santuario de Chimayó is open for visitors from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. October through April, and 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. June through September. A Sunday mass is held at 12:00 Noon. Weekly masses are held at 11:00 a.m. daily June through September and at 7:00 a.m. daily from October through May.

For more information contact:

Santuario de Chimayó

P.O. Box 235

Chimayo, NM 87522

Tel: 505-351-4889

Robert Scheer is a travel writer and editor of New Age Travel. Read Robert Scheer’s blog.